The impetus to create such a framework stems from the reality that the majority of developers who work in our development group, will not be there in 4 years (and most will leave earlier). We also see new developers walk in oblivious of the frameworks we have used in the past. Just in the past four years, Rails has been supplanted by Node.js and Angular/React, and PHP has gone from a “goto” language to an outdated language with only a few purposes. This poses a few issues to these high churn development groups when considering choices for technology stacks in the context of maintainability and future-proofing. Pragmatically, original authors of a project for a student club, for example, will not be in school for more than a few years to maintain the project, and the newcomers will not know how to sustain the technology stack of the project created just a couple years ago.

Sustainable Infrastructure

Motivation

ACM@UIUC is a student-run organization that looks to [….]. We maintain a significant amount of infrastructure for a organization of our size […]. However as we are associated with a university, the members of the organization change every year as students graduate and new ones take their place. In the past our infrastructure was based on a large monolithic codebase which manages all of the member services we have (e.g….). While monolithic architectures have their benefits such as clear model ownership (a-write-once-use-everywhere mentality) making it easy for an up to speed team to make incremental improvements, the inherent difficultly in understanding a highly interconnected system coupled with the high churn rate in maintainers made it challenging to maintain such a project and it means that development efforts were a mad push to get to stable and then hope nothing breaks because no one will try to fix it after a couple years.

Microservices

Our response to this problem was to adopt the aforementioned microservice architecture, which looks to promote modularity and minimization of external dependencies. The main proponents of this architecture include large scale companies like Netflix and many startups. The system breaks down into two groups: clients and services. All components of the infrastructure are completely separate applications running on separate processes in deployment. To prevent client (and service) developers to manage an ever-increasing list of services and their APIs, many implementations of the microservice architectures include what is referred to as an API Gateway. This gateway exposes all the services as a unified RESTful API while managing application level security, inter-service communication, and routing of requests. This approach provides several key benefits:

-

Services are inherently simple. Application scale ranges from a standard 1000-line Sinatra app with multiple database models to a 100-line Node app which simply reads and writes to a YAML file.

-

Any service can be discarded and replaced without affecting other services (provided functionality parity).

-

Third party APIs are easily and securely accessible by any client that can access the API Gateway. This moves the burden off the client developer to juggle tokens.

-

Clients are far simpler because the application logic has been abstracted behind the gateway.

-

Maintainers can focus and own their own codebase.

API Gateway

The key to the microservice architecture is the API gateway. There are many platforms which provide the functionality of an API gateway; Amazon Web Services, Nginx, and others have offerings that manage access to services and coordinate micro-service systems. There also exists a few frameworks to self-host an API Gateway. We will examine in detail Tyk and Kong, two popular options, however, there are others that are language or web framework specific.

Tyk

Tyk is a full-featured gateway that looks centralized much of the common tasks that exist within common infrastructure setups. It does things like having a centralized Authentication provided in the gateway, allows for granular access control to routes and hosts API documentation. It configures its system using a series of JSON objects either held in a database or in a series of files that are parsed and include many options controlling the massive feature set Tyk offers.

Kong

Kong also has a vast set of features and plugins, as also looks to centralize much of the common tasks in managing the infrastructure Kong, however, takes a different approach to its proxy. It only takes a hostname in and relies on the client to provide the host it’s looking for (it does allow for a host proxy though the documentation is not clear as to how that works exactly). Since everything is done through DNS listings, it is very easy to add your service, but it means that it’s hard to come in and see what is going on without the use of its admin API There are many other platforms that include gateway functionality, in addition to other features, such as Docker Compose. However, all these systems are high performance, complex pieces of software that are meant to serve millions of users at once, which is a bit heavy handed for nonindustrial use. Additionally, the use of these systems may require platform buy-in, suffer from lack of ease-of-use and clarity and perhaps require the user to spend money to set up a gateway.

Arbor

We were not happy with the current offerings for API Gateways as many were just too complex to maintain in our organization (again churn being a big factor here). We, therefore, created our own API Gateway framework which we call Arbor.

Arbor is a statically configured API Gateway framework written in Go. It provides the key gateway services, having a full-featured REST proxy all behind its hostname, with websockets and more modern protocols in the pipeline, it manages application level security and simple request sanitization, it also features a human readable service definition format.

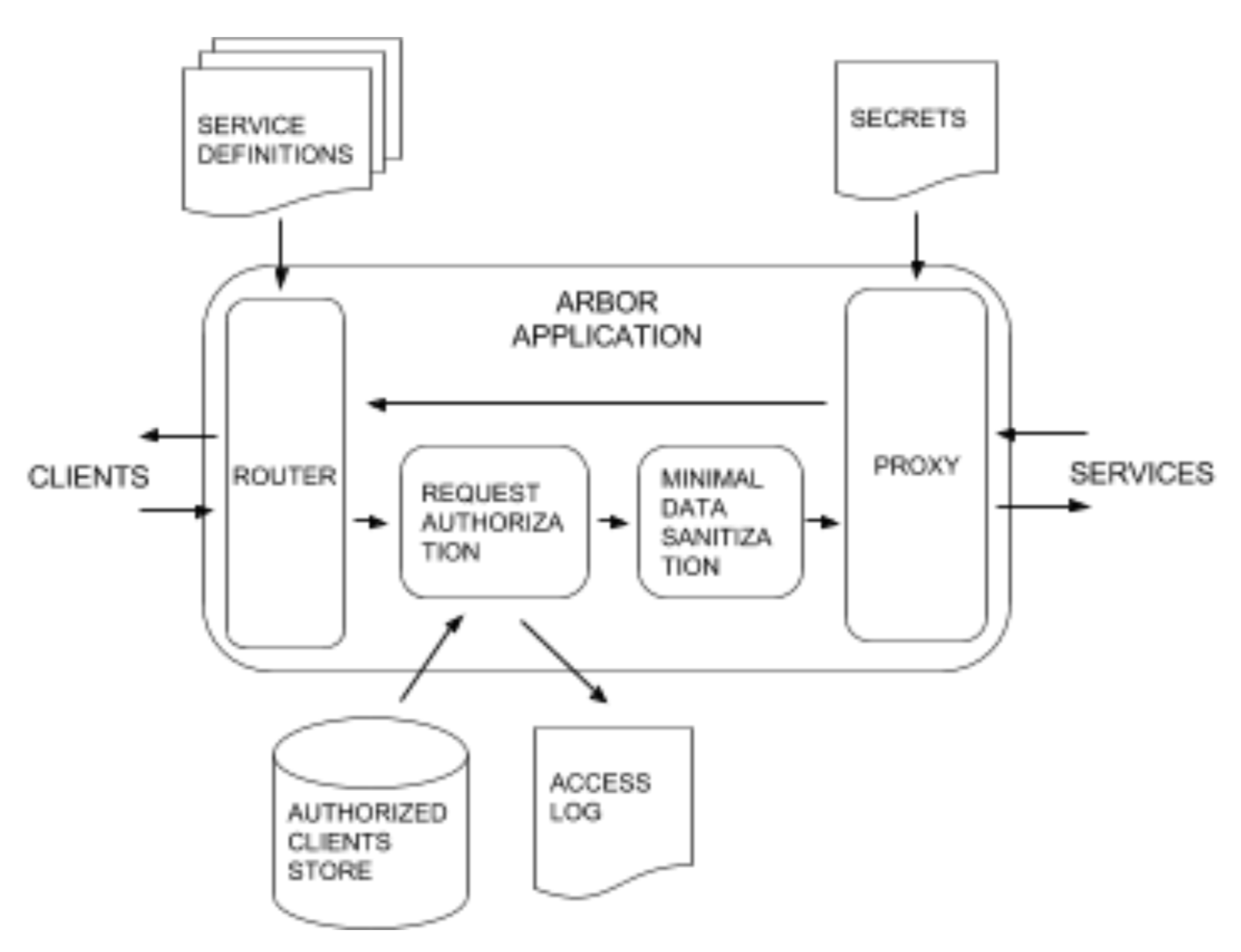

Arbor is broken into four sub-packages, server, proxy, services, and security. The full system architecture is described in Figure 1. and is centralized around the Arbor server. The server manages the execution of the subsystems within Arbor.

The first layer on the server is the router. As of now, the router is vanilla gorilla/mux but we fully expect to need to modify the router to support future development.

Route definitions are user defined through two types defined by Arbor/services, Routes and RouteCollections, in which Routes define a specific route, and RouteCollections encompass a service’s routes. As part of the service definition, the user specifies the proxy handler that would manage the communication between the client and the service from the set of functions in the proxy package.

At runtime these service definitions are loaded into the router and as a request comes in the router hands the request to the appropriate proxy handler.

Before any further processing, if the user enables security features, the next step for the request is to go through two main security features. First is a client authorization verification step. When security features are enabled the gateway requires clients to provide a token generated by the security package. If this is not provided the request is denied at the gateway level. Any successful access is logged in a access log file and then the request is moved on to the second step. We wanted to take the burden off our service and client developers to do proper html sanitization, so we have a module in the pipeline to clean the request. Services are still required to do some validation but we are looking to centralize common tasks.

Afterwards, the request is sent to the proxy server, which will inject any required access keys or extra data in order to fulfil a request. This allows clients to avoid needing to manage a huge set of tokens and keys. The request goes out from the proxy server and then the response is forwarded back to the client.

This means that registering a new service is just adding a file, recompiling and deploying, and authorizing a client is a just simple command as of now. The question of what data is available is answered by the definition itself. Arbor attempts to be simple, making very few assumptions, and is easily extensible.

This new framework and architecture choice has accelerated the creation of new pieces infrastructure in our organization many times over. It has given us the freedom to replace many aging systems with new modern ones without fear of breaking other things. It also gives the developers the leeway to focus more on functionality over sustainability, since it is now expected their code will last perhaps two or three years max. Each service can now range from 100 lines of code to 1000. Our infrastructure is now language agnostic as well. We have a ruby, a python and a javascript developer all developing code for the same system. It is also easier now to replace a system since a spec of what needs to be supported is kept in the schema file for that service. We now have 15 services and two clients all managed through Arbor serving 1000 people.

Future Work

Throughout Arbor’s development, we have uncovered a few issues which should be identified and addressed:

-

Arbor currently only supports RESTful APIs, we are looking to add support for websockets so that the final parts of our infrastructure can come under the gateway umbrella.

-

Documentation generation from parsing schema files would be a welcomed feature so unaffiliated consumers of our API will have documentation other than our repo

-

Improved centralized functionality for things like security is being considered. Currently, there is a simple sanitizer in the proxy pipeline that can be enabled. We have this so that service developers do not need to consider security other than that which is specific to their service. This sanitizer is not very powerful at this point and we must also balance the urge to centralize functionality with not making assumptions about development processes.

We do not expect Arbor to be serving millions; we see it as a Sinatra/Flask to Kong or AWS’s Rails /Django, but we think that this framework will let a whole new set of developers experiment with microservices. It looks to provide the barebones API Gateway functionality and let the developer focus on the application functionality. Ultimately for us, it means we no longer have to race against time to train developers before the lead maintainers leave and that the infrastructure of our organization can now better reflect the needs of its members. We are now more open to one-off contributors, who wish to add one service and leave. When the next web framework of choice emerges, we will have a system ready to accept it with minimal wrestling

The source code is released under the University of Illinois/NCSA Open Source License and on Github

Check it out at https://github.com/acm-uiuc/arbor